Several years ago, my husband, his brother, his writing buddy and I drove down to Las Vegas to see New York Times Bestselling author Terry Goodkind in person. We were devouring his Sword of Truth series at the time, which were about as addicting as that gooey chex-mix stuff we make on New Years Eve (I can. not. stop.). We stayed up until after midnight in reading binges more times than I care to fess up to.

Unlike most of the others attending, I brought along a four-month old baby. I did run into at least one other woman with a baby and we had a good chuckle when we realized both of our babies had names that matched characters in the series (my daughter Rachel was not named after the character, but I’m pretty certain her daughter Kahlan was).

Later we participated in a Q&A section. One thing that stood out to me was something my husband’s writing buddy asked. “Are you ever going to let Richard and Kahlan finally be together?” Goodkind cracked a grin and said (and a paraphrase because it’s been a long time), “Keeping those two apart is what lets me drive a ferrari.”

Which bring me to the topic of this post. Conflict.

Conflict is what Keeps Us Coming Back For More

It seems like one of our main goals in life is to get things under control, save up for retirement, pay off the mortgage, get our kids into college, whatever. But despite our best intentions, life just falls apart sometimes.

The characters in our books are no different. They too are trying to get their lives together, and it’s up to us as authors to do everything in our power to shake it up. In Jerry Cleaver’s excellent book Immediate Fiction, he says that nothing tells us more about characters than how they deal with their troubles. Action is character. Whether they want to or not, conflict draws them out. And that draws us in.

Without conflict, we don’t have a story. If the characters are in a good place and everything’s hunky dory, we as the readers aren’t. Happy lives make lousy novels.

So Cleaver says conflict consists of two elements:

- A want

- An obstacle.

Both want and obstacle must be determined to overcome the other.

This seems like it should be pretty obvious, but this battle is often what keeps us intrigued and glued to the end. Obsessed even. We don’t talk about ball games that ended up in a blowout. They’re forgettable and annoying. We talk about that game that went into double overtime and the basket that swished through the hoop at the last second to win it. Why?

Conflict works because we are so Emotionally Invested

We care about the outcome because we care about the characters. The higher the stakes, the more emotionally gripped you will become. We can’t predict the outcome. It could go either way, and that swaying back and forth, that roller coaster, that drama is what keeps us coming back for more.

In The Sword of Truth series, Richard and Kahlan want to be together. But it seems like everything’s conspiring to keep them apart – duty, physical limitations, other romantic prospects, prophesies, even the gods. It’s the struggle to get past all those obstacles, to see if the “want” is strong enough to endure that keeps us hooked.

Novels are peppered with conflict. Mr. Darcy wants Elizabeth. He overcomes his revulsion at her social and family inferiority (obstacles) to ask her to marry him, only to be refused for his arrogance (obstacle). Later, she must overcome the wrath of Lady Catherine, her prejudice and his humiliation after rejection (obstacles) to get what she wants – Darcy.

Here’s a few more:

• Frodo wants to destroy the ring. It is corrupting him (obstacle).

• Mr. Rochester wants to marry Jane. He has a mad wife in the attic (obstacle).

• Edward wants Bella. He also wants to kill her (obstacle).

• Percy wants to find Zeus’s missing thunderbolt. The person who stole it sabotages him (obstacle).

But it’s not enough to just have conflict.

The Conflict must be Powerful

It’s not just his ability to throw up obstacles that made Goodkind’s writing so addicting, it was making the character’s goals nearly impossible to obtain. He would beat them up, run them over with a herd of elephants and then toss them over a cliff … and that’s just before breakfast. I don’t know how many times I thought I have no clue how they are going to get out of this mess. Which of course raised the stakes, making me more curious and more emotionally involved and I had to read on.

Your characters need to struggle and fight for what they want. It needs to become an obsession. What comes easily is not as appreciated.

So How Can This Be Applied to Your Writing?

Before you even begin a story, firmly establish the main desire (want) and obstacle. Ask yourself what the main character(s) want more than anything?

Say we have a story about a man who wants to establish a relationship with his daughter after the death of her mother. Now let’s throw up the obstacles.

He abandoned his daughter when she was four months old (obstacle). His daughter has grown up despising her father (obstacle) and is only with him because she doesn’t have any other options. He resents the loss of freedom (obstacle) and doesn’t believe he has the capacity to be a good father (obstacle). He feels guilty for what he’s done and doesn’t believe there is forgiveness for his neglect (obstacle). Yet somehow he’s got to be a father to this little girl.

Wow. That’s a lot of obstacles. It’s starting to get interesting because both have a lot of things to work through, especially since his main goal (building a relationship) is in direct opposition to what she wants (nothing to do with him).

The way the characters work through the obstacles are a pivotal part of the story.

Is the father’s desire to be a real father strong enough to overcome his fear and frustrations? Can she ever grow to like him? Can she forgive him? Perhaps even love him?

What to do When You Lose Your Way

If your story feels like it’s starting to drag or losing its way, going back to conflict’s one two punch can be an incredibly effective way to revitalize a stagnant story.

If either want or obstacle is weak, you have no conflict. Both must be equal and strong.

In my example, if the father loses heart and quits trying to have a relationship with his daughter, you have no want, no conflict, no story. So either the story needs to be rewritten so he is focused on the want, or his desire needs to be rekindled so he can recommit to his original intention.

Usually one of these two things – the main character(s) moving toward their goals or throwing up a few obstacles will get the ball rolling.

So ask yourself:

• Are all of my character’s actions focused on their want?

• Is there balance between want and obstacle?

• Do I have scenes that distract from the want (thus the story) that need to be cut?

• Am I considering both internal and external story wants?

• Are there enough obstacles?

Asking these types of questions force you to focus on what’s most important. You may find by cutting distracting threads or adding missing ones that your story is back on track in short order.

How has focusing on conflict improved one of your stories?

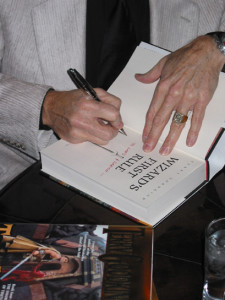

P.S. Don’t you think Goodkind has wizard fingers? I’ve always thought so.